Cultural Consumption Boom

A love story was sparked when Chen Linxiao and Ning Chengfang first met 36 years ago in the dusty corridors of a Beijing bookstore.

The couple, born in the 1960s, had been searching for the same book throughout the city one day, but found more than what they had bargained for by the end of the day. Chen had just claimed the only copy of the book he was looking for at a store and was about to exit when he was confronted by the then-stranger, Ning. Although she pleaded to buy the book off his hands, Chen Linxiao refused, instead offering to lend it to her.

Thanks to that book, their relationship blossomed, eventually leading to marriage.

"Nowadays, many young people maybe wouldn't understand our feelings toward books at that time," Chen said. "In the early 1980s, books were rare. A significant number of people were hungry for books."

Now, as people's living standard increases, the demand for cultural products has also surged. Cultural consumption can improve people's quality of life and make people happier, claimed Chen.

The couple enjoys reading, watching movies, plays and other forms of creative arts. They have even formed the habit of going to cinema during the Chinese New Year holiday, contributing to the country's astronomical box-office records during that period.

New growth engine

Data from the National Bureau of Statistics shows that from 2011 to 2014, the per-capita average cultural and entertainment consumption of both rural and urban residents had increased by more than 12 percent annually.

In 2014, China's per-capita average GDP exceeded $7,000, and residents were purchasing more cultural products.

In that year, Chinese residents' average spending per capita increased by 9.6 percent nominally whereas their average consumption per capita on culture and entertainment rose by 16.4 percent, as revealed through a sampling survey conducted by the National Bureau of Statistics on 160,000 residents in 31 provincial level administrative units across the country.

China has experienced four waves of surges in consumption. The first was in necessities, followed by household appliances such as color TVs and refrigerators, then by automobiles and housing, and most recently, cultural commodities. Tourism and education as well as entertainment are included in the scope of cultural products, according to Jin Yuanpu with the Cultural and Creative Industries Studies Center, Renmin University of China. Jin said that cultural consumption will become new growth point for the economy.

In fact, soaring demand for such products has in turn fueled the growth of the culture industry. Over the past 10 plus years, the industry has experienced rapid development and offered consumers diversified products.

Expanding cultural consumption is necessary and feasible, according to Liu Yuzhu, head of the State Administration of Cultural Heritage.

The Central Government has been committed to spurring the growth of such consumption.

Since October 2011, for example, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC) listed the culture industry as a pillar industry.

In November 2012 and November 2013, the CPC Central Committee also made decisions to carry out reforms in the cultural market.

In addition, in October 2015, the CPC Central Committee approved a proposal formulating the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-20), China's development blueprint for the next five years, which includes the task of "expanding and guiding cultural consumption."

"It can be said that cultural consumption has never received as much attention as it has today," said Qi Yongfeng, a researcher at the Culture Development Institute, Communication University of China. He said that the industry has become an important force behind the current endeavor to push industrial upgrade and economic transformation.

In 2015, the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Finance jointly launched pilot programs to spur the industry. Beijing, Hubei Province's capital Wuhan, Anhui Province's capital Hefei and Guizhou Province's Zunyi have been chosen to be pilot zones.

Beijing's Haidian District, for example, plans to foster online to offline big data platforms, namely through the website Whtianxia.com, which gathers information about retailers in the district.

When users log onto the website, they can get information about movies, shows, books, videos, toys, jewelry and other related products. The customers are then able to get a credit card, jointly issued by the website and Bank of China, with which they can then get deep discount and other bonuses for their purchases.

"The Haidian District has a series of unique policy packages to boost spending on culture," said Chen Mingjie, an official in charge of the district's publicity department.

The Internet era

Internet Plus is currently a buzzword in China, referring to the adoption of Internet technology by conventional industries. The culture and entertainment industry is no exception to the changes, stated Chen Shaofeng, Vice Dean of the Institute for Cultural Industries in Peking University.

"The emergence of the Internet has helped people spend more time online, and as a result, the audience of the traditional cultural and entertainment industry is shrinking," said Chen.

Nonetheless, he also expressed that it has also created a huge opportunity for industrial transformation, through the innovation of business models and channels.

Changes have taken place in the lives of Ning Chengfang and Chen Linxiao as well. Nowadays, they seldom go to bookstores. Instead, they prefer to order books online.

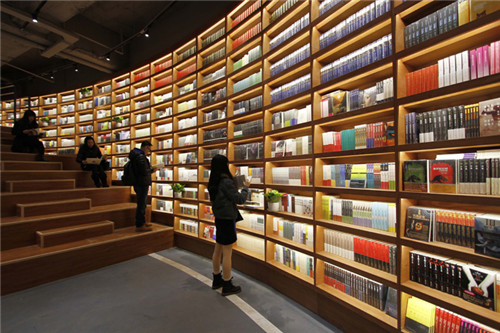

Even so, the couple still have plenty of opportunities to go to physical bookstores. Dangdang.com, for instance, recently announced its plan to open 1,000 brick-and-mortar bookstores across the country throughout the next three years.

"Compared to virtual bookstores, physical bookstores can greatly improve customers' shopping experience," said Yao Dansai, Senior Vice President of Dangdang.com.

The company's plan echoes Chinese Premier Li Keqiang's call for citizens to read more in order to construct a "society of learning" in last year's government work report.

Recently, the CITIC Press Group, a famous publishing group in China, also announced a plan to launch more than 1,000 bookstores nationwide.

Physical books are not as important to Wu Weiwei, Chen and Ning's young neighbor who was born in the 1990s. Growing up in the digital era, he has become accustomed to buying and reading books online.

Although Wu and his wife Sun Hongxi are both avid readers, few books can be seen in their home. Rather than stacking books on bookshelves, they store their "books" in various devices as well as on the cloud, a network of online storage.

According to data from the Ministry of Culture, China currently has 670 million netizens, among which 290 million or one fifth, are literature lovers. "At least 30 million people have published work online, and 1 million are registered writers," Sun said, adding that she herself was preparing to write her own work.

Online literature associations have also mushroomed across the country, while some famous national literature awards such as the Mao Dun Literature Prize are now open to Internet writers. Literature on the Internet was predicted to generate a market value of more than 7 billion yuan ($1.08 billion) in 2015, according to People's Daily .

In addition, young people such as Wu and Sun spend a significant length of time using mobile Internet.

According to Analysys International, a company dedicated to helping traditional companies improve their online marketing skills, Chinese residents born in the 1990s spend an average of 3.8 hours on mobile Internet, with 56.1 percent of that time dedicated to entertainment,18.7 percent higher than those born in the 1980s. The company predicted that by 2020, those born in the 1990s will increase their share of total expenditure in entertainment and education by 10 percentage points.

In January, OpenBook, a company that monitors China's book sales released a report on the country's book retail market in 2015. The report demonstrated that the country's mobile reading market had reached 10.8 billion yuan ($1.66 billion) in value last year, up 22 percent year-on-year. The paper also showed that those born in the 1990s are major players in the market.

Furthermore, book sales through online bookstores also grew rapidly in 2015, up 33.21 percent year-on-year, while total retail book sales went up by 12.8 percent, according to the report.

China currently has 170 million people born in the 1990s. Industry insiders believe that compared with their parents and grandparents, this generation, born in a period featuring rapid economic growth and higher disposable family income, are less inclined to save and more likely to participate in the cultural market. Their influence on the future of the country's cultural development is expected to be significant.

Copyedited by Bryan Michael Galvan

Comments to tangyuankai@bjreview.com

Responsibilities of the SOCAAC

Responsibilities of the SOCAAC Experiencing Beijing 2023

Experiencing Beijing 2023