Common language solves math problem

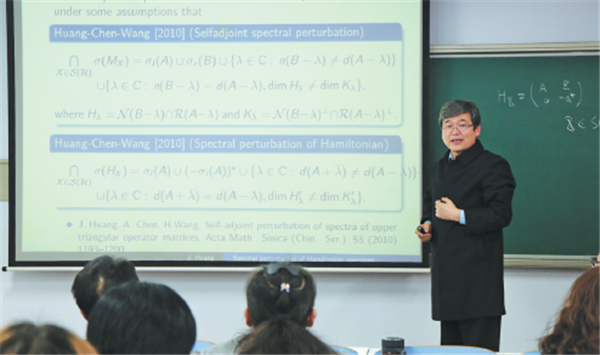

Altantsan teaches at the Inner Mongolia Normal University in Hohhot, Inner Mongolia autonomous region. LIU YUHAN/FOR CHINA DAILY

Mongolian academic who rose from humble beginnings promotes benefits of learning Mandarin and other tongues

Studying mathematics-unlike subjects such as physics and chemistry-doesn't require expensive research facilities or large amounts of money, which is why Altantsan chose it as his academic field when he was a young man.

Born into a poor farming family in the Inner Mongolia autonomous region, Altantsan had a harsh upbringing. With eight siblings, he was forced to do farm work during the winter, wore threadbare clothes, and the family sometimes had to borrow food from neighbors. "Despite all the difficulties, our parents insisted on offering all their children an education, and I told myself I had to change my life," he said.

When Altantsan entered middle school, his older brother was the math teacher and he encouraged his younger sibling's interest in the subject.

In 1981, he scored the highest in gaokao, the national college entrance exam, among Mongolian-speaking students in the Hinggan League and later enrolled at Inner Mongolia University, where he eventually obtained a master's degree in mathematics.

Altantsan went on to gain a doctorate from Dalian University of Technology in Liaoning province for his work on infinite dimensional Hamiltonian systems, a theory that can explain the laws of planetary motion using mathematics, a major innovation in the application of math in natural science.

He was also one of three visiting Chinese math scholars sponsored by the government to study overseas and conducted research work at University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom from 2004-05.

Now age 57, Altantsan juggles multiple roles as a doctoral supervisor, national political adviser and principal of Inner Mongolia Normal University.

Every Friday afternoon during the school semester, Altantsan hosts a symposium on campus about Hamiltonian systems. The weekly seminar, which has been going for 25 years, is open to young math teachers, postgraduate students and doctorate holders.

The research of Altantsan's team has been published in academic journals in more than 10 countries, including the UK and the United States. He also leads six projects sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Language struggle

However, his path to academic success was not easy. Though a top student at high school, Altantsan found university difficult, as all classes were taught in Mandarin. "It was natural for me to learn Mandarin the moment I encountered the problem. The reason was obvious. If I'm good at Mandarin, I will have more opportunities," he said.

Altantsan also taught his students the benefits of learning a new language.

"Children from ethnic groups can better show themselves and better sustain their cultures," he said.

"Besides, all ethnic groups belong to one big family, so it's important to boost communications by popularizing the country's common language."

As a teacher, he has supervised 18 doctoral students, most of whom were from ethnic groups. In 2018, his team of Mongolian-Mandarin bilingual math teachers was listed as one of the national-level high-quality innovative teaching groups.

Erdenebukh, 44, a professor at Hohhot Minzu College, is a former postdoctoral student of Altantsan. He said his former mentor is fluent in Mongolian, Mandarin and English, which played an important role in both his work and study.

"One time, our team invited an expert from the UK and Altantsan hosted the meeting in English. We were able to see the functional benefits of another language," he said.

"It's like a bridge, which not only links people together but also knowledge," he said, adding that learning a language can also play a significant role in personal development.

Wu Deyu, 43, said the use of Mandarin in his hometown in Horqin Left Wing Middle Banner, Tongliao, Inner Mongolia, was minimal, even though all the residents started learning Mandarin in grade three.

In 1995, Wu, along with 19 other Mongolian-speaking students, began to study applied mathematics at Inner Mongolia University. Altantsan, who had returned to his alma mater after completing his doctorate in Dalian, was one of the bilingual teachers at the university.

"He is very attentive to young people. When I was a student and then became a teacher, he gave me a lot of good advice," Wu said. "He always tells us that the mother tongue is like a house, and other languages are like windows-the more languages you can speak, the more of the world's beautiful scenery opens to you."

Wu, who now works at the Inner Mongolia University, was the first Mongolian doctoral adviser taught by Altantsan.

As for Altantsan, he says the Inner Mongolia Normal University is playing a major role training middle and high school teachers in the region. The university also cultivates Mongolian language teachers for other provinces such as Heilongjiang, Jilin, Gansu, Qinghai and Liaoning, he said.

"The country attaches great importance to the education of teachers and ethnic groups. If we can cultivate more good teachers, there will be more outstanding professionals," he said.

Print

Print Mail

Mail