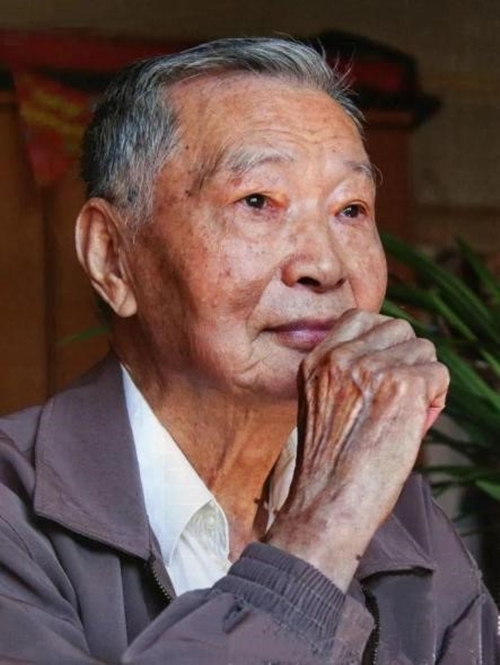

Wang Wencai: The 'most unassuming academician'

Wang Wencai [Photo/mmcs.org.cn]

On November 16, as the leaves were falling off the trees in Beijing, Wang Wencai passed away at the age of 96. His life was closely intertwined with plants, having published 28 new genera and 1,370 new species, making him one of the scholars in China who identified the most new plant taxa. He dedicated his life to establishing "archives" for plants, yet he avoided the limelight. He won the prestigious first prize of the National Natural Science Award twice but never mentioned this to his close relatives. For the last ten years of his life, one of his eyes was blind, unbeknownst even to his daily assistant. Moreover, he battled four types of cancer during his final decade. Despite these challenges, he relied on an eye with declining vision and an old magnifying glass to write over a million words of papers and works.

Specimens, specimens

Wang Wencai examines plant specimens at the Institute of Botany. [Photo/mmcs.org.cn]

At the foot of Xiangshan Mountain in Beijing, sits Asia's largest herbarium — the Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The herbarium houses more than 2.9 million plant specimens, over 40,000 of which were identified by Wang, making him one of the herbarium's top contributors. However, years of closely examining the fine structures of plants through magnifying glasses and microscopes took a significant toll on his eyes.

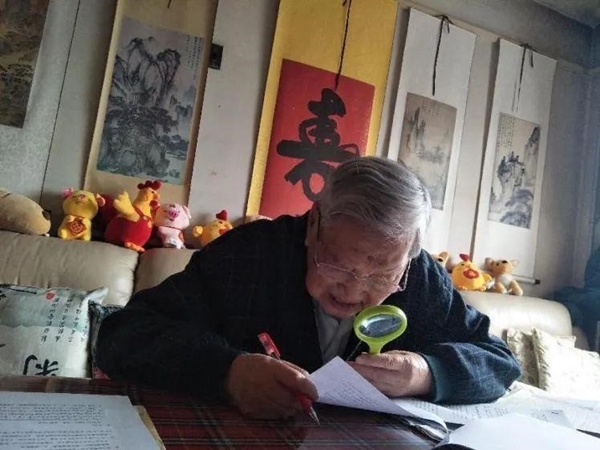

Wang Wencai works at home with a magnifying glass. [Photo/mmcs.org.cn]

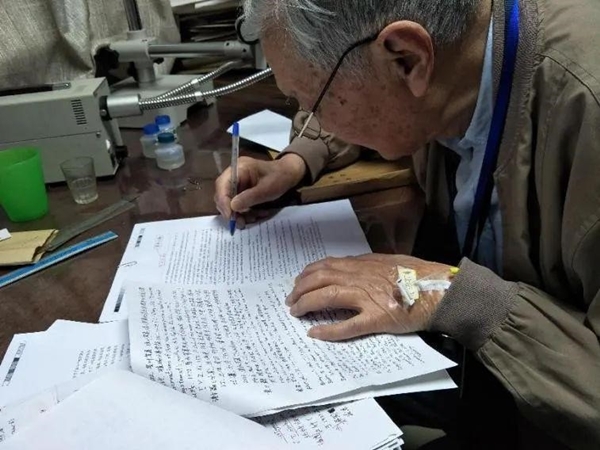

After the Lantern Festival in 2019, Wang, then 93, gave his assistant Sun Yingbao a photo of himself working at home. In the photo, he was reading a document with a magnifying glass. Realizing that something was wrong with Wang's eyes, Sun took him to the hospital the next day. After examining the left eye and noting its blurred vision, the doctor asked about the right eye. "My right eye has been blind for ten years," Wang softly explained. Sun was stunned. For a decade, Wang had never mentioned his blindness, his eyes showing no sign of abnormality apart from the occasional use of a handkerchief. In early 2020, the publication Selected Works of Wang Wencai: Additional Essays included 77 papers totaling more than 1.5 million words, all written after he had lost vision in his right eye. Reflecting on the millions of words in his articles and specialized books like The Genus Deinostigma from China and The Genus Kingdonia from China, completed with only one eye, Sun could no longer hold back his emotions. He rushed out of the examination room and cried bitterly. On the drive back from the hospital, Wang murmured, "While I can still work with the help of a magnifying glass, I need to finish writing The Genus Delphinium from China. I'm afraid much of the follow-up work will depend on you in the future." Sun gripped the steering wheel tightly, biting his lips to hold back his tears. The photo of Wang working with a magnifying glass now hangs in Sun's office as a constant reminder of Wang's dedication.

Wang Wencai continues to take the shuttle bus to work even during intravenous therapy. [Photo/mmcs.org.cn]

Wang Wencai collects plant specimens in Xinduqiao, Kangding county, Sichuan province, in August 1963. [Photo/mmcs.org.cn]

Researching plants was always Wang's top priority. He spent 19 years leading the compilation of Illustrations of Higher Plants of China, a monumental work documenting 15,000 species of higher plants in China. At the time, it became the world's largest illustrated work of its kind. He also spent 40 years compiling the Flora of China, contributing to the documentation of over 1,000 plant species. He gained global recognition for his expertise in classifying difficult plant families like Ranunculaceae, Gesneriaceae, and Urticaceae. The gradual publication of Flora of China, spanning 80 volumes, 126 books, and over 50 million words, stunned the entire botanical community. It remains the largest and most comprehensive botanical work in the world.

The 'most unassuming academician'

Wang won the first prize of the National Natural Science Award in 1987 and 2009. This award is considered the crown jewel of scientific achievements, rarely given and often left vacant due to its high standards. Winning it twice is extremely rare, yet Wang remained unperturbed by the honors. He never mentioned the awards, and both times he had someone else collect the certificates on his behalf. "He believed it was a collective achievement, and he merely did his job," recalled his son Wang Chong. Wang Wencai accepted the highest academic honor of being an academician with the same composure. One day in March 1993, despite being retired, Wang Wencai came to the institute as usual to observe specimens. Upon entering the office, he heard he was nominated as a candidate for an academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Instead of rejoicing, he frowned, worrying it might affect his research time. Many people said Wang Wencai was both the "most like" and the "most unlike" an academician. He wore decades-old jackets and worn-out shoes, waited for the shuttle bus for years, and addressed younger colleagues as "Mr." He lived humbly, treating others with respect, with a deeply ingrained humility that seemed almost stubborn.

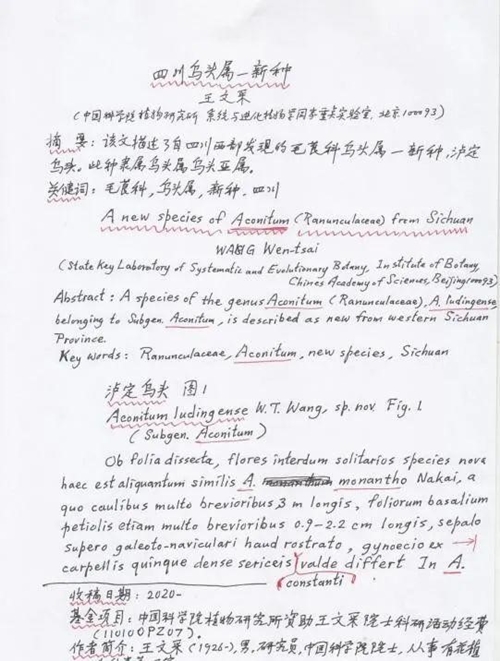

Wang Wencai's handwritten manuscript penned at the age of 94 [Photo/mmcs.org.cn]

Wang Wencai poses with one of his landscape paintings in November 2020, at the age of 90 (now hanging in the Metasequoia Building of the Institute of Botany).

Wang Wencai enjoyed sitting on his old, light-yellow sofa, listening to Beethoven's symphonies. He also loved painting, having studied under the artist Wang Xinjing during middle school, with a particular fondness for the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) painter Tang Bohu's art. Some of his large landscape paintings, created when he was 90, now hang in the Ginkgo Building and the Metasequoia Building. Tranquil in nature, Wang Wencai sought neither fame nor material wealth.

He opens the door for outsiders

Wang Wencai recognized and cherished talent, treating everyone equally regardless of their background. Seventy-year-old Li Zhenyu was one of Wang's handpicked disciples. With simple attire and unhurried demeanor, Li focuses solely on plants. Four decades ago, Li was a young worker at the Fujian Agricultural Machinery Factory. Each weekend, he would take lunchboxes up the mountains to collect plant specimens, often sending his preliminary identifications to Wang Wencai and other experts for verification. Wang Wencai noticed that most of Li's identifications were correct, even including some plants not previously recorded in Fujian. Sensing Li's potential despite his middle school education, Wang Wencai recommended him to his superiors. After a rigorous assessment, Li was officially transferred to the institute. To help Li catch up on university-level courses, Wang Wencai even agreed to teach voluntarily at Capital Normal University for two years. "Mr. Wang was very patient," Li recalled. "Though strict in academic matters, he only used a slightly stern tone to correct repeated mistakes. This restraint motivated me to work even harder." Today, Li is a prominent figure in plant taxonomy. In June 2022, Li and his colleagues named a newly discovered wild cherry species "Wencai Cherry" in honor of their mentor.