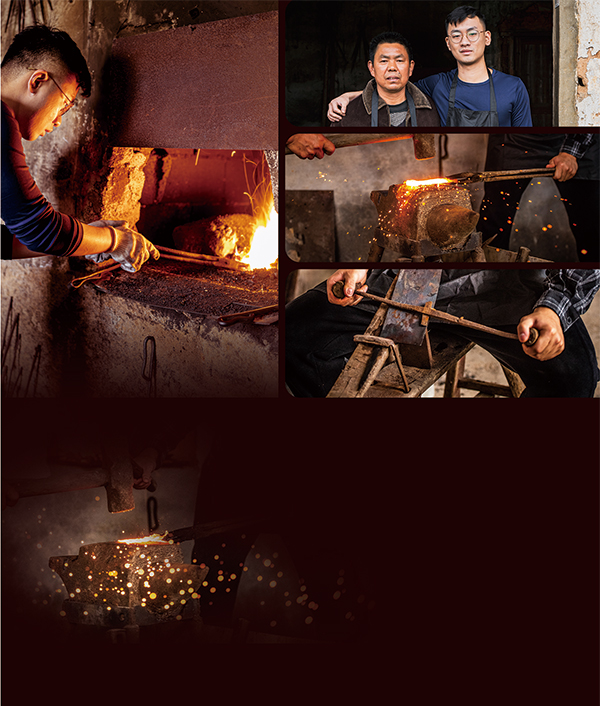

Clockwise from left: Xiao Chao sets fire to heat iron blades to make traditional Chinese cleaver at his workshop in Changsha, Hunan province, in March 2022. Xiao (right) poses with his colleague at his workshop in March 2022. Xiao makes traditional Chinese cleaver at his workshop in September 2022. [Photo provided to China Daily]

There are only about five people making handmade traditional Chinese cleaver in Changsha, Hunan province, and 29-year-old Xiao Chao is the youngest among them, with the average age of the others being over 60 years old.

Xiao was born in the Laodaohe region in suburban Changsha, where the history and techniques of making Chinese cleavers date back for more than 500 years.

To make a Chinese cleaver, the iron and steel blades need to be heated to more than 1,000 C, and two pieces of iron blades need to be repeatedly hammered and quenched with one piece of steel blade more than 2,000 times.

These techniques were recognized as a provincial intangible cultural heritage in 2016.

The Chinese cleaver, also known as a Chinese chef's knife, is a staple of the Chinese kitchen, rivaled in utility only by the wok and chopsticks. Chinese people have used the cleaver for everything from slicing, chopping, mincing, and scraping.

Xiao's father runs a cleaver store in Changsha, so he is familiar with the industry and has been fascinated by making cleavers since childhood.

He started to learn the techniques in 2014 at the age of 19 and has become a full-time cleaver maker for almost 10 years.

Learning the techniques has had its difficulties. With temperatures rising to 1,000 C, the heat is the first thing he must cope with, especially during summer days when the temperature in Changsha can easily rise to 40 C. Moreover, the pure physical labor of hammering has been exhausting.

Making a cleaver is time-consuming. Xiao said he can make at most two cleavers in a day. It's also dangerous, as evidenced by his hands, which are covered with injuries from blade cuts and burns.

His life has been occupied by work. He makes cleavers in the morning, manages his cleaver shop in the afternoon, and sells cleaver products on the short video platform Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, in the evening.

"I work almost 12 hours a day and seldom take a break, even over the weekend," he said.

Xiao has been passionate about improving his techniques, and learning the process of making different new products has also been fulfilling for him.

"I have persisted for almost 10 years because I really like the job. Whenever I acquire a new technique or create a new cleaver, I feel a strong sense of satisfaction," he said.

However, Xiao also needs to face the reality that handmade cleavers do not yield much profit with the prevalence of machine-made ones being sold at cheap prices.

He said the average price of his cleavers is about 100 yuan ($13.81) each. If the prices drop any lower, his business cannot make a profit.

To expand the sales channels, Xiao has opened an online store on Taobao and also sells products via livestreaming on Douyin.

His followers on Douyin have now surpassed 13,000. By posting videos of his daily life making cleavers and explaining the history of the Laodaohe cleaver as well as its differences from other cleavers, Xiao has garnered many die-hard fans who would buy all his new products.

"They treat handmade cleavers as artworks as each one is different and contains the efforts of the workers," Xiao said.

Mu Jia, 40, from Xi'an, Shaanxi province, is one of Xiao's fans.

"I believe each cleaver is unique and a piece of art. Only those who truly understand it can make a high-quality Chinese cleaver, and Xiao is one of them," he said.

Mu says he likes cooking, and knives are very important tools for him. He became a fan of Xiao in 2022 and has bought almost 50 cleavers from him because he believes they are better than all the other brands of knives he has used.

However, he said that the Laodaohe cleavers need more advertising and promotion to prevent them from becoming a fading brand.

The government also needs to invest more in protecting products of the country's intangible cultural heritage; otherwise, they might be replaced by machine-made cleavers someday, Mu added.

Zhou Zhenke, 39, lives in Manila, the Philippines, and is also a fan of Xiao's products. He was sent to work in Manila by his company last year and has been missing Chinese food very much. After trying various foreign knives which he didn't like, he bought several cleavers from Xiao's livestreaming sessions, and it took over a month for them to be shipped to the city.

"I have bought more than 10 cleavers from Xiao. The Chinese knives have made the Chinese food more authentic, which is soothing for someone living overseas," he said.

Zhou was impressed by Xiao's focus on craftsmanship, but he also believes that additional promotion is needed for the cleavers to be known by more people.

Xiao's products are very creative, and the style has been updated to cater to modern tastes, Zhou said. If more people know about them, they will become popular, he added.

Xiao said it is also difficult to find young people interested in learning to make Chinese cleavers as it requires hard labor and working in tough conditions, but he will continue the work and try to find new ways to promote his products.

Since 2022, Xiao has been receiving media coverage, which has contributed to the sale of his cleavers. However, persisting in the trade is not easy for him due to the demanding physical labor and the reluctance of other young people to learn the craft, he said.

The busy work has also made it hard for him to find suitable life partners. "My entire life currently revolves around making and selling Chinese cleavers, so there are few opportunities for me to meet potential partners. Plus, I'm too much of a romantic and idealist to go on blind dates arranged by my parents," he said.

Whenever he can squeeze in some spare time, Xiao also likes singing and playing the guitar and piano. He has posted videos of himself singing and playing the guitar on Douyin, which have also received positive feedback.

"If the business really cannot sustain itself, I might consider becoming a professional singer," he said.