Embroidery often called rare living fossil

"Busy, tired but happy every day," is how Fu Xiuying describes her life. From the Li ethnic group on Hainan Island, Fu has won fame both at home and abroad for her double-sided Li brocade embroidery, weaving artworks using highly refined techniques that span 3,000 years.

Fu, 52, is entering the busiest period of her life since she was named in 2010 by Hainan authorities as a representative inheritor of double-sided brocade. UNESCO listed the brocade in its first endangered cultural heritage group in 2009. At the time there were only five masters of the brocade in China.

During the three-day Li new year holiday in late March, Fu received orders worth more than 110,000 yuan ($16,000), enough to keep her busy for the year.

And more orders are coming in, as the traditional Li brocade - often described as a rare living fossil - is used from everyday artifacts to high-end commodities highly valued by world-wide collectors.

She also teaches brocade techniques in a number of schools, universities and training centers in Li villages. The Li were the earliest settlers on the island and they were the first cotton growers in China.

Li women hold a special place in the country's textile industry development for their spinning, coloring, design and weaving and embroidering.

Despite her busy schedule, Fu relishes the opportunity to look after her 18-month-old granddaughter Ding Dang, and enjoys weaving her artwork under her watchful eye.

"When Ding Dang is able to understand more, I will tell her stories about the Li people and the brocade, prized tributes to the royal palace ever since the Han Dynasty (BC 206-AD 220)," said the proud grandmother.

Fu's potential encouragement for her granddaughter is in marked contrast to her approach to her elder daughter Fu Lirong. When her daughter told her that she would like to learn the traditional skills after graduation in 2008, Fu spurned the idea.

"I know how hard the job is for a woman and what was more depressing was that at the time I did not see a future for someone to follow that path," said Fu.

The Li ethnic group accounts for about 1.3 million people, and around 90 percent live on the island. Fu learned the traditional skills from her grandmother but it seemed to be a dying art due to social development and the introduction of modern textiles.

The number of people classified as masters of brocade techniques plunged from 50,000 in the 1950s to around 1,000 about 10 years ago.

"We display our ethnic history by embroidering symbolic designs on the colorful Li cloth. It's like a 'historical book"', Fu explained.

"In 2006 I lost my job as a grain store worker in Baisha Li autonomous county, my hometown. Worse, my husband passed away, leaving our two daughters. I had to shoulder the family burden myself," said Fu.

"I turned to my aunt for help. She was a master of embroidery and encouraged me to pick up and pass on the traditional skills. Under her guidance, I mastered the four basic skills for brocade making - spinning, dyeing, weaving and embroidery, a complete set of highly complicated techniques which very few have mastered," said Fu.

The time spanning 2006 to 2008 were the hardest years and she slept for just two or three hours a day to devote enough time for weaving and embroidery.

But the hard work and devotion paid off.

"A young man, who was intrigued by Li brocade at an exhibition in the United States, came to Baisha in 2013 especially for one of my double-sided tapestries. It depicted the landscape of the local Beauty Mountain," said Fu. She sold it for 68,000 yuan and the money gave her the confidence and freedom to continue her work.

Fu said she was impressed by the efforts of the Hainan government to save the techniques.

"The government's policies to protect the brocade heritage gave me new hope," said Fu.

"Attending the training courses arranged by the State for intangible cultural heritage inheritors has broadened my vision and inspired me."

In the past six years Fu has trained 356 primary and middle school students, as well as 2,368 women in mainly rural areas around cities such as Sanya, Wuzhishan, Baisha and Baoting in brocade skills.

The moon, stars, rivers, mountains, birds and flowers, even pots and bowls can inspire creations.

The double-side embroidery is both time and energy consuming. "A small piece of tapestry needs at least 15 days, a skirt needs one month to weave, and a traditional Li suit needs between 10 to 12 months," said Fu.

"Some people suggest simplifying the designs and skills to save time. But I refused. Baisha's skills and designs for double-side embroidery have been passed on for hundreds of years and can not be simplified. Simplification will lose the charm, characteristics and the market," said Fu.

Fu Lirong, her daughter, eventually won over her mother and has also become an inheritor of the embroidery in Baisha county. She understands her mother's passion.

"My mother is quick to learn. She cares about everything that could inspire her embroidery. Sometimes I saw her get up at 2 am, picking up her embroidery to catch a sudden inspiration.

"At first, I learned from my mother without letting her know and when she saw how determined and how interested in the traditional skill I was, she began to teach me."

The brocades are like the Li language and a cultural label and the designs are expressions of their passion, imagination and expectations.

"I used to worry very much about the future of Li brocade culture. Now the government has set up so many training centers and special villages to pass on the traditional techniques, and I have so many students around the province, I feel at ease.

"My students are very devoted and serious. They will be good teachers in the future," she said.

mazhiping@chinadaily.com.cn

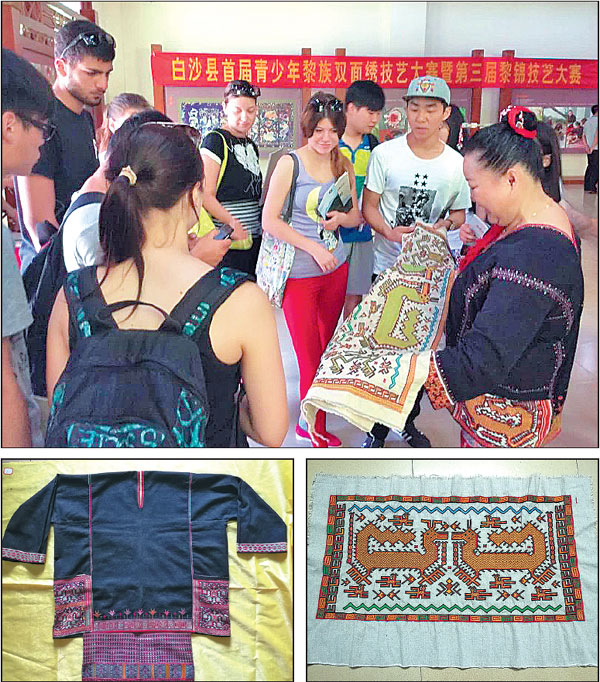

Fu displays her tapestry to tourists. Her intricate embroidery work and one of her dragon-themed double-sided tapestries.Provided To China Daily