Family shakes off past as village drinks to arrival of better days

Wei Zhenling used to make annual trips to her ancestral home in Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region. However, for Wei, her elder brother, sister and their parents, these were difficult journeys.

Their destination, an isolated ethnic Maonan community, lies tucked away in the karst mountains of Huanjiang Maonan autonomous county.

To ensure they arrived before nightfall, their parents woke the children in the early hours at their apartment in the county seat for the family to catch the first train of the day to the area.

The most torturous part of the trip then followed.

The last leg of the journey involved five hours of walking uphill, burdened by gifts for friends and relatives they had not seen for a long time.

The meandering, rocky roads almost robbed Wei of the curiosity she had about her cultural identity.

"I was sustained during those trips by a sense of tradition and a subconscious feeling of homesickness," said Wei, a chief prosecutor from Guangxi.

She is the only ethnic Maonan member of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference National Committee-the nation's leading political advisory body that met in Beijing earlier this month at the same time as the National People's Congress, the top legislature.

Last year, the country's 107,000 Maonan people, the majority of whom live in Huanjiang and an autonomous township in neighboring Guizhou province, escaped absolute poverty, as the Communist Party of China aimed to eradicate domestic poverty before celebrating its centenary this year.

Wei said isolation fueled the widespread impoverishment that her people experienced for generations.

During journeys to the ancestral home, Wei's father, a member of the Maonan ethnic group who became a physics and math teacher after graduating from a local teachers' training college, told stories of traveling the same route once a semester in his younger days to reach the only school in the county seat.

"When he finally saw the county seat from a hilltop, my father said he cried out loud," Wei said.

She added that her heart sank when she learned that many Maonan people, after leaving the rolling mountains for better lives, seldom, if ever, returned.

Isolation was largely to blame, and it also served to reinforce an ultra-conservative mindset, forcing locals to cling to a primitive way of life.

"Money does not work here-you need to barter for daily necessities," Wei said.

Her aunt, an ethnic Maonan, culled pigs and cattle for bartering and also made sure she kept an adequate supply of rice and grain to make liquor.

Wei's mother, an ethnic Han who can understand but does not speak the Maonan language, depended on her father to barter for groceries in the village. Her mother said she tried several times, but "no one would sell things to an outsider".

Used to urban living, Wei had to sleep under the same roof as grunting pigs and lowing cattle. However, what bothered her the most was the overwhelming stench.

Water crisis

In the village, water was the most precious commodity, especially during the dry, cold winters. "My mother told us to treasure every drop," Wei said.

The water the family members used to wash their faces was saved for hand-washing later before being given to the livestock.

In such rocky terrain, where there are few rivers, water is only found many meters underground.

The older generation depended on rainfall collecting in a large puddle near the village as its source of water. Wei said hygiene standards were questionable, which could explain the higher mortality rate among newborns at the time.

In addition, the puddle dried up in winter, when rainfall was scarce, forcing locals to travel to another village to use a trickling fountain.

The difficulties obtaining water led to Wei's grandfather-then the village head-to launch blasting operations in the mountains to search for supplies underground.

Water was found, but her grandfather lost sight in one eye during this work.

"When I descended the stone steps into this darkened cave three dozen meters below ground, I feared it could collapse any time," Wei said.

Irrigation was impossible, leaving the villagers few options other than to grow corn and soybeans, which can better survive drought but can only meet basic needs.

Rural improvements

Last year, authorities announced that Huanjiang had escaped poverty, and each family now had access to tap water.

In Wei's ancestral village, which is home to several thousand Maonan people, tap water was obtained by pumping supplies from a well drilled by the local authorities.

Huang Bingfeng, head of the county and a member of the Maonan ethnic group, said that in a nearby community of 20,000 Maonan residents, the authorities built a ditch to divert water from a river more than 12 kilometers away.

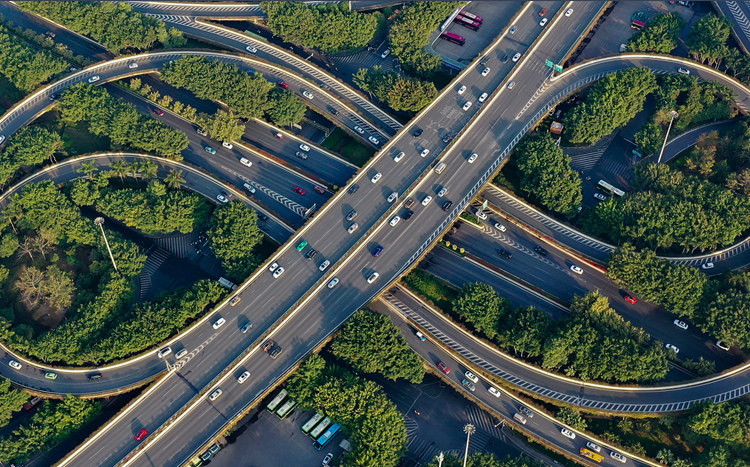

Paved roads have also been built as part of a drive to bolster rural infrastructure.

Better connectivity and irrigation have allowed locals to grow rice, mulberries and pomelos. Some residents have started work in the transportation industry as a result, while others have accepted government incentives to raise cattle and pigs, which has proved commercially successful, Wei said.

The Maonan people are among 28 smaller ethnic groups nationwide pulled out of poverty by November.

"My grandparents have died, so we seldom travel back home now. If we do, it is for the Tomb-Sweeping Festival," Wei said, adding, "We now drive to our old house."